Yesterday, both the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of the UK cut their benchmark interest rates to record lows. This is especially incredible in the case of the UK, whose Central Bank over 300 years old! You can see from the following chart that both Central Banks have more than made up for their respectively slow starts in easing monetary policy by effecting several dramatic rate cuts, following the example of the Federal Reserve. The baseline UK rate now stands at .5%, only slightly higher than the Federal Funds rate, and slightly lower than the 1.5% ECB rate.

Given that they have essentially reached the terminus of their monetary policy options, all three Central Banks are exploring further options aimed at pumping money into their respective economies. The Fed has already “announced a program to buy $100 billion in the direct obligations of housing related government sponsored enterprises (GSEs) — Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Federal Home Loan banks — and $500 billion in mortgage-based securities backed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae.” As I wrote in a related article, “this was quickly followed by repurchase programs, lending facilities, investments in money market funds, and option agreements, all of which were designed to supplement its ‘traditional open market operations and securities lending to primary dealers.’ The Fed’s efforts also work

ed to ease the liquidity shortage in credit markets abroad by entering into swap agreements with several foreign Central Banks suffering from acute Dollar shortages.” In conjunction with the rate cut, the Bank of the UK, meanwhile, will pump £150bn directly into UK credit markets through liquidity support, buying public and private debt, and asset purchases. “The main purpose of quantitative easing is not to send the money supply into orbit but to stop it from crashing…the broad money held by households has risen at a worryingly slow rate over the past year, and holdings by private non-financial firms have actually

been dropping.” In contrast to the monetary programs of the UK and US, the ECB has thus far refrained from the kind of liquidity support that would necessitate printi

ng new money. Instead, “the central bank will continue offering euro-zone banks unlimited loans at the central bank’s policy rate until at least the end of this year.” The interest rate cuts were announced simultaneously with a spate of macroeconomic data, which collectively paint a bleak picture. Eurozone growth is projected at -2.

7% for 2009 and 0% for 2010. The current unemployment rate at 8.2% and climbing. The thorn in the side of the EU is represented by eastern Europe, where growth is falling at an alarming pace, dragging the EU down with it. While EU member states have pledged to intervene if one of their own falls into bankruptcy, it’s unlikely that they would intervene similarly if a non-EU member state went bust. The UK economy is similarly desperate, having contracted at an annualized rate of 5.8% in the most recent quarter. The wild cards are the real estate and financial sectors, the fortunes of which are increasingly intertwined.

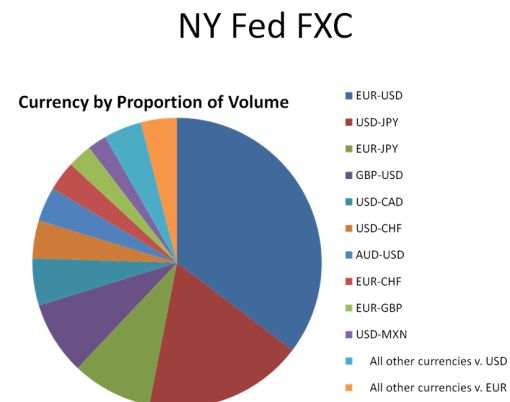

So what do the forex markets have to say about all this? Economists have used the dual phenomena of risk aversion and deflation to explain the interminable weakness in the the Pound and Euro. Everyone is surely familiar with the notion of the US as “safe haven” during periods of global financial instability. The deflation hypothesis, meanwhile, suggests that the ECB (and to a lesser extent, the Bank of UK), fell behind the curve when easing liquidity. The ECB, especially has harped on inflation as a reason for cutting rates more quickly. Given that investors are now more concerned with capital preservation than price inflation, it follows that they would prefer to invest where Central Banks were more vigilant about deflation (i.e. the US).

Personally, I think that the continued declines in both currencies, in spite of steep interest rate cuts, indicates that the deflation hypothesis is bunk, and investors remain fixated on risk aversion. By no coincidence, the temporary rebound in US stocks that took place in January was also accompanied by a bump in the Euro. (See chart below).

I think this mindset is reasonable, but only in the short-term. Given the current economic environment, I don’t think investors (and currency traders) can be faulted for ignoring the possibility that quantitative easing and liquidity programs will have to be funded with the printing of new money, which would be inherently inflationary. Many comparisons are being made with Japan, whose ill-fated quantitative-easing program succeeded only in inflating a bond-market bubble and vastly increasing Japanese public debt. According to one columnist, “it’s hard to argue that quantitative easing ended deflation; high oil prices did that. Meanwhile, the economy cured on its own most of the structural problems such as excess capacity and too much debt associated with the deflationary environment.”

In short, with a medium and long-term investing horizon in mind, I think the ECB’s approach to dealing with the credit crisis is more conducive to monetary stability. Thus, when investors grow weary of the idea of US as safe haven, they will no doubt focus instead on fundamentals. At which point, the ECB will likely be rewarded for fulfilling its anti-inflation mandate, in the form of a stronger Euro.